The notebook, hidden under carrots and beef stock at the grocery store, seems to watch Cassandre, as if it already knows what she intends.

On the ride home, the blue notebook sits beside her purse at the edge of her vision. She wonders if writing it, telling it, will make it melt like something made of snow. Will it make the thing ordinary?

But she has to get it out, has to tell someone about him. It is like mice running inside, battering against her ribs. Might as well tell it to herself.

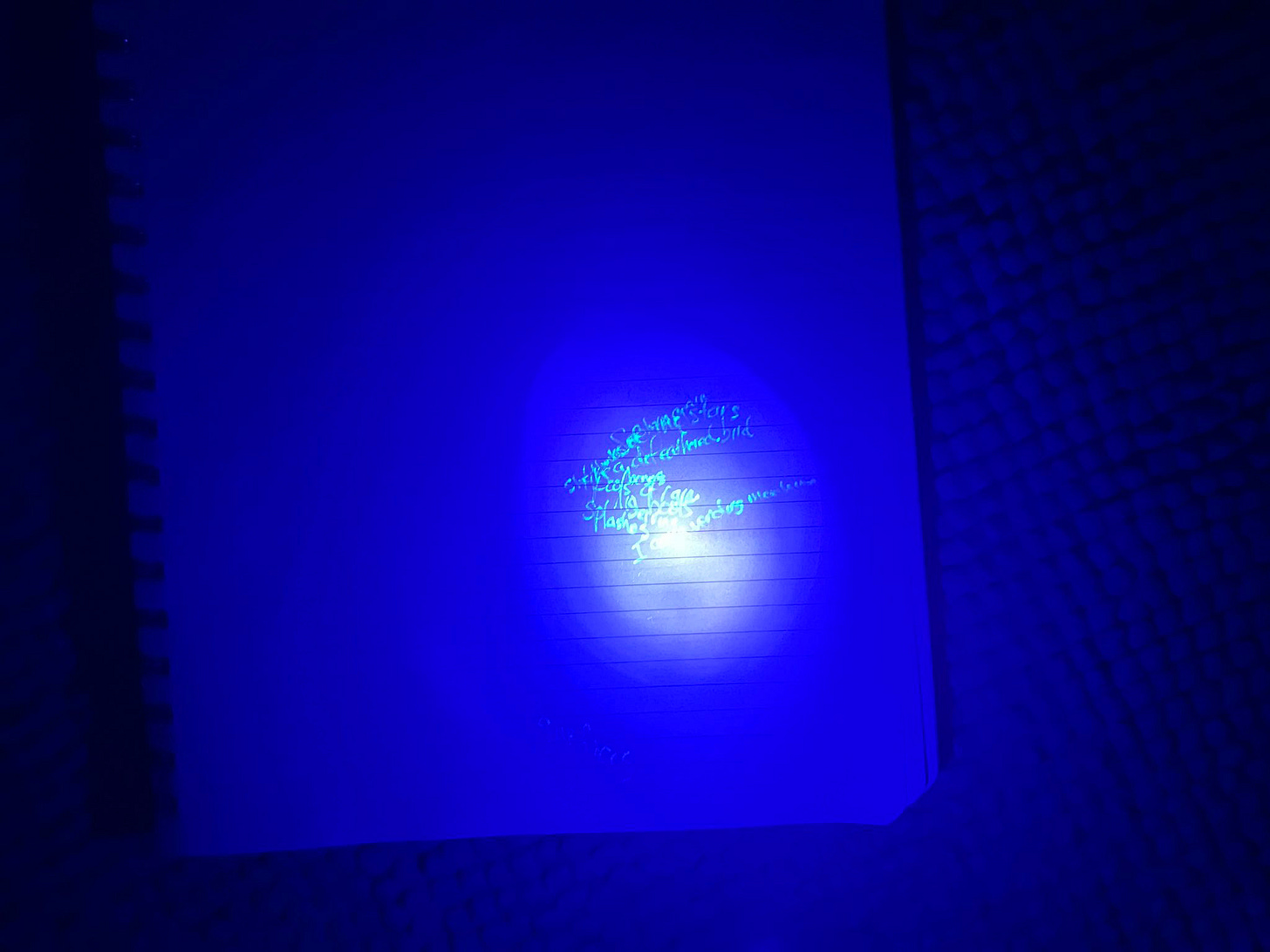

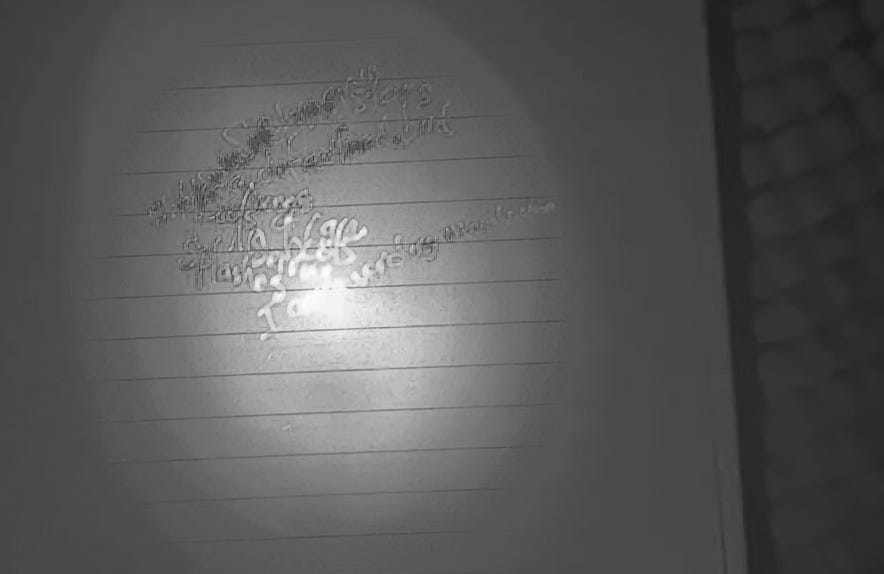

She takes her time putting the groceries away, extending the seconds, delaying the moment she opens the notebook. The invisible pen has been in the jar for years. She gave it to Sarah when she was still little, even letting her draw on the walls—a secret between them.

She pulls it from the jar now, hidden among the ballpoints, and tests the ink on her finger. She flicks on the tiny ultraviolet light at its tip. The small x on her pointer glows yellow in the violet beam.

She opens the blue notebook on the table, checks her watch. Almost an hour. She will hear Steve’s car in the garage.

She sits at the kitchen table with the notebook open, the paper glaring white in the sunlight. Her mind is blank.

She writes:

It’s more about what it did to me than what actually happened.

It was just one time, it’s over now.

She looks up again, across the living room to the perfectly aligned portraits, the glare from the sunlight outside erasing the faces, the birch tree swaying, throwing birdwing shadows across the glass.

Unbuttoned, skin opened, freezing water. Foot fallen asleep, plunged in ice. Wind moving inside ribs.

The page is still white, as if unmarked.

Through the open laundry room door: stacked boxes, Sarah’s handwriting in black marker—Kid Toys, Give Away. By the end of the year, Sarah will be gone, her move has already begun.

I am going to need something else.

She shuts the notebook with a careful press of her palm, hides the pen among the ballpoints in the jar.

She listens for the car, checks her watch. There he is, right on time. She can script his movements, like Sarah’s storyboard characters pinned to her wall: every move of his entry. Door opens, jacket on the third hanger, closet left a sleeve’s width ajar, a sigh, a hello from across the room, disappearing into his study.

He has her memorized too. Sitting where she always sits, the hi honey, dinner will be ready at 6. How, when Steve is gone, she will close the closet door he’s left ajar.

It wasn’t always like this. Maybe if she pulled out the old photos of themselves, put them in the frames to remind them that once there was so much to say they stayed awake until dawn. She remembers looking at the headlights streaking on the ceiling and the words they said to one another almost visible in the texture, like the letters were pressed into the stucco.

If only there were a photo to frame like that.

Sitting at the river on her lunch break, watching the surface of the water, the scum of yellowed foam, she imagines writing on the surface of the water.

She told her boss, can’t get the lunches anymore, have to go looking for the cat. Except now the cat was found and she hadn’t told. Not yet. She wanted this hour, this extended hour that eased into two.

The lost cat was how I found him.

They found the cat here, living off moles and small birds. Someone had seen the flyer and told them where to find it.

Cassandre remembers tacking the flyer to the bulletin board at the sandwich shop, the way she felt him watching as she pinned it. Her phone buzzed in her hand, unknown caller, and when she looked up he was standing by her flyer, phone raised, smiling—his laughing eyes on hers.

Cassandre sits with her wrapped, untouched sandwich on the concrete, her shoes neatly placed beside her, her bare feet dangling over the water.

She looks out at the water for a long time and then checks her watch. She’s late. Walking back to her car, uneaten sandwich rolled into her hand.

Aren’t you going to have any?

She is about to start the ignition but stops. Not yet.

She throws the sandwich to the waiting gulls and they gather around it, picking hard with their open beaks. A dropped fish is ripped open. Its body raw and flayed, sparkling multicolor in the sun and she thinks of him again.

His whiter skin under his clothes looking raw, like a defeathered bird, how it had made her laugh, and how he laughed with her, not even knowing why.

She smooths out the sandwich paper and begins to write directly on the oil spots:

the stories they told each other about their lives, lying across the bedspread at the Glasswing Motel

his:

winter lake steaming, dropping his robe and diving in/ cold breath in hot lungs/ heart stopping a second/ sight going black

hers:

eyehole burned through the tent to see the stars / the smell of firewood on Steve’s jacket / waking to rain pooled in their boots.

She keeps going, her hand moving faster, words gone off the edge of the paper and now she is writing on the upholstery, the words disappearing even as she marks them. She crumples the sandwich paper into a ball, placing it carefully in the ashtray and starts her car. The seat is clean, blank, as if nothing ever happened.

She is going through the motions. Serving dinner, taking the hot plate out of the oven, heat steaming her eyes like they are made of glass. Doesn’t even really feel the burn on her palms.

Sarah is talking but Cassandre isn’t listening, she is thinking of the graffitied walls of the factory near where she’d parked, the vibrating lights at the sandwich shop, the smell of cold meat, the feeling of drinking cold water in her throat.

And suddenly Cassandre hears her daughter, freezes, the spatula dripping lasagna cheese and hears Sarah’s talking about persistence of vision, “…we think we’re seeing a continuous image, but our eyes fill in the gaps with what we saw before.”

Sarah says she has abandoned the film she’s been writing for months, tore up the storyboard. Steve is shocked, angry even: Why tear it up?

And Sarah says: It was all wrong. I have a new idea.

A long tendril of cheese is still dripping, and Cassandre says, “That’s it. Keep going.” And the two of them look at each other for a long time.

Steve mumbles something and pushes his chair back, carrying his plate into another room. He’s been doing that more these days.

“Aren’t you going to have any, Mom?”

“No, go ahead…”

Sarah leans in, “He’s just… asleep. He’ll wake up when I’m gone, I know he will. Just needs to find himself again.”

How does one go about doing that?

At her desk Cassandre watches the clock. The nails of her coworker hammer the keyboard. Plastic donuts on the counter. A fly wheels above them, its iridescent wings mirroring the sprinkles.

Aren’t you going to have one?

She is sweating, it is hot, airless.

The phone ringing, blinking green, now faster, angry red. Yes, hello, yes, wait one moment please.

All the sounds come together in one single humming texture. She notices the light playing on the wall, reflected off the fountain in the court outside. She tells herself she will just take a minute, take a breath of cold air, won’t even bring her jacket, she’ll come back. But she keeps walking.

The cold wind blows open her blazer, fights at her buttons, feels like it cuts right into her.

Next she’s in her car, and then she is back at the river again, walking out on the jetty.

She takes her pen and places it against her wrist, she writes:

Nerve.

She continues writing her thoughts on the concrete railings. She thinks of her grandfather. He used to do this, near the end, didn’t he?

Ballpoint on the headboard, on the bathroom wall, on his sheets, on his skin.

She had asked her mother what it said, what he’d written. Her mother shrugged, surprised, and said “nonsense.”

Just nonsense.

Sarah sets up the old projector, reels from her grandparents’ attic scratched and inked into until they are a dark, flickering wash of bodies in water.

On the wall: the old lake. Cassandre and her brothers in slashes of light, blots of dark, splashing.

Cassandre begins to laugh—a full, round laugh—and realizes it's how she used to laugh, back then. Sarah watches her, nodding.

Steve says, “You’ve ruined the film.”

“No,” Cassandre says, surprising herself with the authority in her voice. “You’re missing the point. She turned it into something else.”

And she begins laughing again, that strange deep rolling laugh.

She sits in the driveway with the groceries, a paper bag of chicken thighs balanced on her lap. She tears the paper open, eats with her hands. The bones are slippery, she pulls at the soft cartilage with her teeth, stretching the skin.

She begins writing on the windows, on the windshield, then her purse, her shoes.

She steps out on the driveway and crouches, writing on the cement, the garage door, the siding of the house.

The car is still idling, wheels creeping forward, almost not at all. She watches them in the corner of her eye, the little slip forward.

Steve appears suddenly in the driveway.

“What the fuck is going on here?”

She laughs, lifts the pen, says: nonsense.

He ducks into the car, swearing, slamming the car into park. He takes the pen from her hand and goes inside, shaking his head.

She pulls another pen out of her pocket and continues.

Later she serves dinner. Sarah’s place at the table is empty—she’d left a note without saying when she’d be back. Cassandre has set two perfectly aligned plates, both empty. Just words scrawled imperceptibly across the white ceramic.

Steve sits, baffled, angry. She watches him calmly.

He doesn’t even say anything, just gets up, but before he storms off, he stands there looking at her, head shaking.

Later, she goes to their bed, the light from her telephone is blue and watery. He is already asleep, snoring softly. In the dark he looks like a younger version of himself. She puts her hand on his arm, whispers, “we should talk again,” but he turns over and she is left there looking at the back of his head.

She drives down to the river and leaves the headlights on, flooding the water with light. Bats and birds flash across, wingbeats spliced into frames. The rain begins, light and blowing, freezing, drenching her. The headlights pouring across the water, making the air look lit up, almost sparkling. The rain runs into her eyes and mouth, penetrating her clothes, soaking into her skin. She stands there shivering, imagining her skin softening, going transparent like paper. She wants to write it, right there on the rain… it’s raining right into my bones.

She writes him a note, in real ink, leaves it at their sandwich shop. She turns over the picture of the no longer missing cat. The image bleeds through, the ink warping the paper. She writes his name and: GLASSWING INN.

Now she waits there, Tuesday, Wednesday, what day is it now? She writes on raised velvet paisley, the mirror, the bedspread. She writes about the lake with her brothers, the splashing, the light from Sarah’s projector, writes about the feeling of water on her skin, about her teeth burying into meat. The weight of his body on hers, the cold of him, like drinking water…

Then she lays out and watches the light from the pool on the ceiling.

Then he comes.

She loosens his tie, unbuttons his shirt and pants, her hand sliding down his chest, down his hip. She points to the bed, undresses slowly, showing him her whole body, handing him the black pen.

She tells him she wants words everywhere—everything he sees, every thought in his mind. And he slowly, achingly slowly, begins to cover her with his words.

If you enjoyed this piece, I’d love for you to read one of my latest — I’m especially proud of this one:

Cassandre turns every surface into a page because silence is killing her. The notebooks, the sandwich paper, the windshield, even her own skin are a protest against being erased inside her house and her marriage. By the time she lets another man inscribe her, it is less about desire than about proof she still exists. Great short fiction, Sandy!

Excellent work S, I particularly liked the brief stacatto sentences in the middle. The variation of sentence structure and rhythm was very effective. The overall theme of writing as incription of desires (invisible/made visible)... I'd write more but I can't really see what I'm typing right now (weird font colour problem)